Sam Ben-Meir “Destruction of Juukan Cave a Loss to Humanity”

Published on September 22, 2020

The Anglo-Australian multinational company Rio Tinto – the largest iron ore mining company in the world – demolished two 46,000-year-old Aboriginal rock shelters in May. What is particularly disturbing about this event is that Rio Tinto was apparently acting entirely within the law, which is to say that this kind of tragic and wanton destruction will continue to happen unless stricter regulations are enacted. The sites were located on the ancestral lands of the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura, or PKKP, people in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Anthropological studies commissioned by Rio Tinto itself confirmed that the caves were of “the highest archaeological significance,” containing an “enormous museum of information about [the PKKP people’s] ancestors’ work and lives.”

The conflict between industry and heritage that we are witnessing today is of course not a new phenomenon. Indeed, in Australia, it has been a persistent problem since at least the early 1960s when the mining and extraction of iron ore in the Pilbara region began. But the struggle can and should be seen also within the larger context of the marginalization, subjugation and decimation of the Aboriginal peoples that has been the story of their ongoing plight since 1788 when British settlers began colonizing the Australian mainland. Not until 1965 did most Aboriginal Australians enjoy full citizenship or voting rights; and it would take six more years before they were included on the national census. Australia’s indigenous people constitute only two percent of the population and yet are 28 percent of Australia’s prisoner demographic.

The unrelenting destruction of indigenous heritage sites is entirely consistent with the same ideology that has driven Australia’s aggressive campaign of deforestation. Both are expressions of one and the same policy of uncompromising colonization. Over the last 200 years Australia has lost 25 percent of its rainforest, 45 percent of open forest, and 32 percent of woodland forest. In fact, among developed countries Australia has one of the highest rates of deforestation, which has led to the annihilation of much of its native wildlife. Twenty percent of Australia’s mammals, 7 percent of its reptiles, and 13 percent of its birds are listed as extinct, endangered or vulnerable. According to wilderness.org.au, 1,000 plant and animal species are presently at risk of extinction.

The obliteration of the Juukan Gorge caves certainly represents a devastating loss to the PKKP – but it is a tragic loss for the world as well. These rock shelters fostered our understanding the human beginnings of art, religion and culture, indeed the dawn of humanity’s self-awareness – yet, as anthropologist Marcia Langton observed, “their significance for further understanding of deep human history is a matter that was willfully ignored by Rio Tinto.” What consequences did Rio Tinto suffer for its recklessness? Several of its executives will lose their bonuses, totaling roughly $6.7 million (USD 4.9 million) – a mere slap on the wrist which in the absence of legislation will do nothing to protect the few similar sites that remain.

Dr Lawrence Owens, an archaeologist and anthropologist from the University of London, told Mining Technology, “There is no other way of putting this – the destruction of Juukan Gorge cave was a travesty and a disgrace.” He added, “It is difficult to fully express the magnitude of what this site was, what it meant, and how its destruction has impacted upon us all.” The caves that Rio Tinto blasted have been understandably compared to Stonehenge which is some 5,000 years old – yet the comparison does not really do justice to what we lost, given that this site was nearly ten times older than that. Moreover, unlike Stonehenge which belongs entirely to a bygone era, these caves have been continually occupied by the same peoples, generation after generation, over these tens of thousands of years. They were a kind of “encyclopedia of the Aboriginal people.”

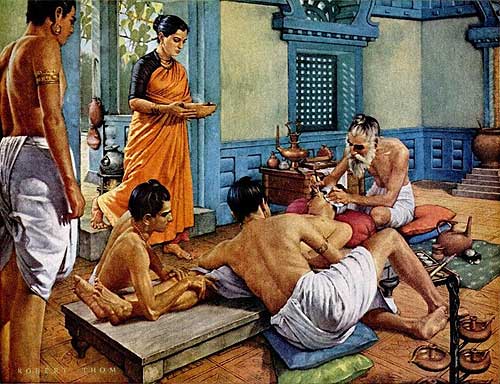

One of the most precious and astounding discoveries in the cave was a 4,000-year-old length of plaited human hair, woven together from strands from the heads of several different people. This remarkable find established through DNA testing a direct link to the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura traditional owners living today.

Rio Tinto received permission to conduct the blasts in 2013 under Section 18 of the WA Aboriginal Heritage Act. It is an offence under Section 17 of the Aboriginal Heritage Act (AHA) of 1972 to excavate, destroy, damage, conceal or in any way alter an Aboriginal site. However, under Section 18 landowners may apply for consent to breach the restrictions established under Section 17. Accordingly, Rio Tinto was not operating illegally or flouting the law.

David Ritter, former principal legal officer for the Yamatji Land and Sea Council, observed that, “It is a myth, expressed by the objects of the Aboriginal Heritage Act that the main purpose of the legislation is to protect Aboriginal heritage. It may be more accurate to describe the AHA as an act to regularize the obliteration of Aboriginal heritage… It is legislation by the non-Indigenous community for the non-Indigenous community that creates a superficial veneer of protection for Indigenous interests. The result is that the colonizing power can continue to do with Aboriginal places and materials exactly as it wants.”

We know that this desecration could have been avoided altogether because during a federal parliamentary inquiry, Rio Tinto’s CEO, Jean-Sebastien Jacques stated that there were four options to expand the iron ore mine in the area. Three of the options would have avoided the rock shelters, but the mining company chose the more destructive alternative as it allowed them to extract $135 million (USD 97 million) worth of iron ore, a profit that exceeded the other choices. They opted for the route that allowed the company to mine “8 million tonnes of higher-grade iron ore,” according to Mr. Jacques.

It has long been recognized that Australian laws do not adequately protect Aboriginal heritage sites. The Dampier Archipelago of Western Australia is home to thousands of Aboriginal pictographs, and perhaps the oldest surviving rock art in the world. Indeed, Australia’s Indigenous art represents the longest uninterrupted tradition of art in the world – going back over 50,000 years – with examples having been found that depict long-extinct megafauna; including the Thyalacine (Tasmanian tiger) and Fat-tailed Kangaroo. Representations of the now-extinct marsupial lion have also been found in the Kimberley region of Western Australia.

The extraordinary rock art of the Dampier Archipelago easily constitutes the largest and most diverse gallery of petroglyphs in the world. Recent archeological research confirms that the Dampier Archipelago and Burrup Peninsula (formerly known as Dampier Island) contains the largest concentration of ancient rock art in the world. However, the rock art of the Burrup Peninsula has been physically destroyed by construction and eroded by industrial emissions, continually “under threat due to high concentrations of acidic and nitrate-rich pollution from nearby industrial complexes,” according to a 2017 report published by the Journal of Archeological Science.

What we know is that the cultural and scientific significance of the rock art is comparable to ‘such world-renowned prehistoric art galleries as the caves of Lascaux in the Dordogne, and Altamira in northern Spain’. The tragedy is that we are losing the cultural riches of these region before we have had a chance to truly understand their significance – for, as a 2006 report prepared for the National Trust of Australia (WA) states, “numerous petroglyphs and other archaeological features have been destroyed and a significant portion of the extraordinary heritage of the Dampier Archipelago has been irretrievably compromised without any clear understanding of what has been lost.”

Aboriginal people represent the oldest continuous culture in the world – adequate protection of that culture will be encouraged when we respect and appreciate the wisdom of the Aboriginal people and their genius for ‘living with and fostering their environment.’ We may, for example, view Aboriginal rock art as disrupting the dualistic, Cartesian view of landscape, offering instead an embodied approach which recognizes that we “do not live in an environment. Such a position immediately posits our separation. Rather we have an environment and we are part of it and it is part of us… We are… immersed.” In Animism: Respecting the Living World (2005), Graham Harvey observes that, “[W]e have far too many experiences of the aliveness of the world and the importance of a diversity of life to fall in step completely with Cartesian modernity.” We need to broaden the interpretative lens with which we view Aboriginal rock art and see that in fact it represents an important challenge, and possibly a corrective to an overly dualistic ontology, which pits nature versus culture, mind versus body and human versus non-human.

Sam Ben-Meir is a professor of philosophy and world religions at Mercy College in New York City.