Streets Of Gold

Published on March 17, 2020

Niraj Srivastava

Much has been written about the city of Lahore, and a huge train of history rides within the ancient walls of the Walled City enveloping historical lores, sparkling culture and the dying embers of a tolerant region now lost to the shrill cries of myriad ‘isms’.

The Shahi Qila of Lahore stood majestically at this cradle of tolerance, commerce, sensuous art and the martial spirit of a giant web, which spun everyone and everything into its own effusive, elastic culture.

The Shahi Qila of Lahore stood majestically at this cradle of tolerance, commerce, sensuous art and the martial spirit of a giant web, which spun everyone and everything into its own effusive, elastic culture.

The city saw its glorious years when it remained the Darul Hukumat or Capital of the Mughal empire for many years, especially under emperor Akbar. It was deemed as the main Mughal bastion to safeguard its northern and NW dominions extending across Kabul and Kandahar, and always maintained a sizeable permanent garrison.

The Lahore Fort by itself has a long history of more than 1500 years as the abode of the Hindu Rajput dynasty of the Solankis, then the invading Afghans and Turks, The Mughals, the Sikhs and also the British.

Though the Hindu dominion of the Lahore Fort ended with the Solankis migration to India in 1175 AD, and the marauding forces of Mahmud Of Ghaznavi occupied the fort, it was completely destroyed by the Mongols in 1241 AD, and then rebuilt several times by the Mamluk dynasty, Sayyeds and finally the Lodi dynasty before being captured by Babur, who established the Mughal empire. It is worthy to note that all these constructions were of mud and limestone and were not of any defensive use against artillery and matchlocks which had begun making their appearance by early fourteenth century.

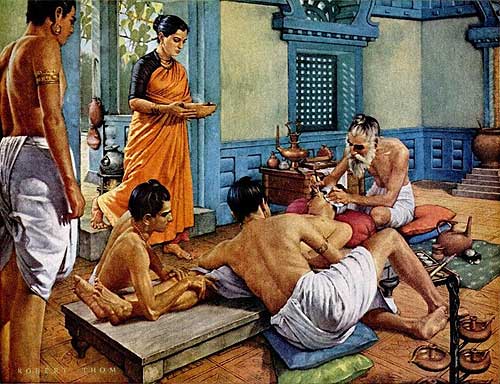

The present Lahore Fort structure was actually built by emperor Akbar sometime around 1575 AD, when he established Lahore as a major garrison to defend his northwestern territories. The mud walls and structures were replaced by stones, bricks and masonry, and lofty walls and palatial buildings came up as a vibrant Mughal court replete with the emperor’s massive harem, legions of court officers and an enormous army took quarters there.

The citadel is divided into sections, each with its distinctive use and quadrangle. Every Mughal emperor from Akbar to Aurangzeb contributed to the erection of new palaces, gates and gardens. Emperor Jahangir, with his eclectic tastes and fondness for beauty had the majestic Picture Wall created with glazed tiles, faience mosaics and frescoes in vivid colours. This breathtaking, stunning depiction extends for 1450 feet (440 m) and rises to a height of 50 feet (15 m), providing us with an awe inspiring colorful canvas of roughly 72,500 square feet!

The Lahore Fort’s importance and allure cannot be encrypted in a few paragraphs, and hence, we move forward to that period in March 1597 when the Shahi Qila was engulfed in a devastating fire which forced emperor Akbar, prince Salim and the royal ladies to repair to Kashmere for four months, but provided unheard of riches to the Lahoris.

The month of March had set in and the capital was brimming with anticipation of the forthcoming Navroz festivities. Wrestlers, dancing troupes, jugglers, musicians were all streaming in from far corners of the dominion and beyond, hoping for a chance to perform before the emperor. Merchants from as far away as Persia and Tazkhistan, Uzbekistan, were reaching Lahore laden with perfumes, richly embroidered silks and the especially luxuriant and intoxicating wine from Isfahan.

The nine day long Navroz festivities during the Vernal Equinox was one of the most sought after and celebrated period in the Mughal calendar, and everyone from the common peasant to the mighty nobles made sure to attend the festivities and present their nazraana to the Sovereign.

Into this mad milieu rode in horses, elephants, cheetahs, goats and fighting gamecocks to entertain the populace with their skills and bravery, sometimes verging on the foolish. Huge kitchens were set up within the fort and outside to feed the teeming thousands, as the royal Ahadis, magnificent in their gold braided uniforms of red and purple with plumed helmets, practiced their archery and cavalry drills for the big day.

In the Fil Khana or Elephant stables, the humongous war elephants like Ram Prasad, Fateh Jung and Siyah Kol were fed with opium mixed rice and sugarcane to guarantee a scintillating, bloody fight on the banks of the Ravi, witnessed by the emperor from his riverside Jharokha. In the mahouts home, lamentations and mourning rituals were observed since it was certain that the mahouts would not survive the clash of the behemoths.

It was a sunny morning on March 26th, 1597, when emperor Akbar was enjoying an elephant fight immediately after his dispensation in the Diwan-i-Aam (Hall Of Public Audience). The sun was still an hour away from high noon, and the breeze from the riverside was cool and soothing. Emperor Akbar, attired in his favourite colours of red and white with a golden cummerbund sat in the imperial Jharokha. His turban of red silk was glittering with a white heron’s plume and a girdle of diamonds wound around the folds.

His sword, Fateh-Ul-Mulk lay by his side as he peered intently at the warring elephants. Suddenly, shouts of alarm were heard from behind and the trumpets from the naubatkhana let out a series of warning hoots. Soon, the huge war drums joined with their feverish tattoo announcing a grave danger.

Akbar lunged for his sword and moved swiftly through the corridors towards the Maidan-Diwan-e-Aam (Garden Of Public Audience) located in the south of the fort, from where the shouts were coming. The Shahi Qur, or the emperor’s royal bodyguards made up of chosen nobles and carrying his personal arms and insignia had arranged themselves around him in a protective shield.

As they drew nearer, the smell of burning linen and gusts of smoke and hot air hit them. Raja Man Singh of Amer who was supervising the decoration of the mandap for the emperor’s ceremonial weighing against gold and silver, rushed in with his Kachhawa troops, swords drawn.

Performing a quick kornish, he almost shouted in his haste, ‘Your Majesty, a long torch affixed to a pole fell on a stack of silk and muslins. It caught fire, and has spread like a serpent climbing and leaping upon rolls of silk, gossamer and golden streamers. It is like a demon now.’

‘What was a lighted torch doing at this time of the day?’ roared Akbar.

‘Your Majesty, it was being used to heat the lye for adhesive purposes.’ So saying, Raja Man Singh, a navratna of emperor Akbar resolutely barred his way towards the conflagration. Akbar, comprehending the loyal Kachhawas plea, swiftly turned towards the imperial harem.

In less than twenty minutes, emperor Akbar had ridden out of the burning fort seated atop his favourite war elephant Hawai, closely followed by prince Salim and the other senior ladies of the royal harem.

The gates towards the river Ravi had been opened, and teams of slaves and troopers were passing buckets of water to douse the destructive flames. From the main Akbari gate, horses, camels and elephants were deployed to transport barrel loads of water from the river.

The fire spread from the Maidan-e-Diwan-i-Aam to the east and southeast where the imperial offices and Tosha Khana or the Royal Treasury were located. A wall of fire also remained in the north central part of the fort, lapping away at the imperial rooms.

The fort burned for four days, and the foraging fire having entered the imperial suites and the Royal Treasury steadily melted the gold and silver inlays on the walls and roofs, while furniture made of gold and silver ran in small rivulets down the stony passages and into the stony streets outside the fort. Gold and silver coins, chests full of exquisite ornaments were all consumed in the Treasury and surreptitiously found their way to the street outside through creases and dents in the flag stoned corridors.

The Ulemas were the first to wake up and find the culprit; they blamed the emperor’s decision to permit a Jesuit Church near the Lahore Fort as the reason for this calamity. Akbar remained unmoved, though Jahangir had this Church closed in 1614.

For several days, the people of Lahore were busy with shovels and chisels, scraping the molten gold and silver off the streets – for the streets of Lahore, for a few brief days in March 1597, had really become paved with gold!

The writer is the Author of The Course of The Mughal Series.