The Evergreen Melody Lives On

Published on February 23, 2019

It was during the second decade of the fifties that a young girl hailing from Sivasagar just enthralled the audience at Latashil Bihu Function in Guwahati with her mesmerising voice. There was some magical attraction in that voice.

She was Dipali Barthakur who, just after a year or two, became a Guwahatian and won the hearts of the masses in every nook and corner of the State with her spellbinding songs. As a junior artiste, Dipali Barthakur, with her intrinsic politeness and humble attitude could gather profound love and affection from a lot of senior artistes of the State. She would, sometimes, approach the famous and well-known artistes and learn a song or two with outmost sincerity and eagerness.

Then, at the peak of her enviable popularity, Dipali Barthakur lost her unmatched voice. It was an irreparable damage for the music scenario of Assam. Yet, the only consolation is the heartfelt love and recognition showered on Dipali Barthakur by legions of fans and admirers in Assam for her music talent.

Then, at the peak of her enviable popularity, Dipali Barthakur lost her unmatched voice. It was an irreparable damage for the music scenario of Assam. Yet, the only consolation is the heartfelt love and recognition showered on Dipali Barthakur by legions of fans and admirers in Assam for her music talent.

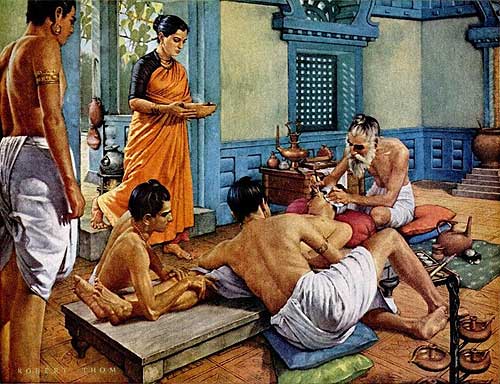

Dipali Barthakur was born on January 30, 1941, at the Nilamoni Tea Estate. Her father was Bishwanath Barthakur, who worked as the manager of the tea estate, and her mother was Aaimoni Barthakur. As the youngest among six brothers and sisters, she lived in a cloistered environment with her elder sisters Rebati, Nirmali and Putuli, and elder brothers Bhupen and Bhaben. When she was a little girl, her father had suffered from severe acidity. And since there was no medical facility in the tea garden, he was shifted to their maternal uncle’s home in the Amolapatty locality in Sivasagar. The family too followed suit. But her father couldn’t recover from his ill-health, and one day, he passed away. Dipali Barthakur was just two-and-a-half-years old then. The family never returned to the tea garden again and stayed behind at the maternal uncle’s place.

They lived with their great grandfather, prominent writer and social reformer Hemchandra Barua, who wrote the first Assamese dictionary ‘Hemkosh’. His nephew – Anandaram Barua, was their grandfather, their mother’s father.

Dipali Barthakur began her studies at the Amolapatty LP School and her high school studies at the Phuleswari High School. She was very fond of music since childhood. Devotional songs rendered by her mother and grandmother were her primary source of inspiration, and shaped a life deeply rooted in traditional values. In Seuji Samaj Sangeet Vidyalaya, which is situated near their house, Parag Dhar Chaliha and the then head master of the school, Atul Sarma used to teach music, and Dipali was quite diligent in acquiring the best of what she was taught. Back at home, her brothers Bhupen and Bhaben taught her singing by playing the harmonium. In 1956, when she was in Class-VII, she was adjudged the Best Singer in a music competition held at Dibrugarh.

Then in 1957, Dipali Barthakur got the chance to sing a few songs in the famous play ‘Charihejar Bosoror Asom’, written and directed by Parag Chaliha. It was Chaliha who introduced her to Phani Talukdar, the then Programme Executive of AIR. And, on his invitation, for the first time, Dipali Barthakur, who was studying in Class-IX then, recorded a song at AIR, Guwahati, in 1958. The song written by Lila Gogoi was ‘Mur Bupai Lahori Napaisu Ahori’. She passed the audition and recorded her first song as a graded artiste of AIR, Guwahati, which was written and tuned by the legendary lyricist Luit Konwar Rudra Barua. The song was the evergreen ‘Samai Pale Aamar Phale Abar Ahi Jaba’.

In 1960, she took admission in the I.A. class of Cotton College. After that, she enrolled in the Handique Girls College for her degree classes in 1962. But after just three months, she shifted to B. Borooah College mainly because of her affinity towards eminent writer, poet and lyricist Nirmal Prabha Bordoloi, who was a professor of the college.

By that time, two songs written by Bordoloi, sung by Dipali Barthakur and tuned by her brother Bhabendra Barthakur had achieved enormous popularity, becoming enduring classics. One was ‘Sunor Kharu Nalage Muk’ and the other was ‘Kon Sei Rupavati Jai’. The collaboration spawned more other songs, which became immensely popular as well, including ‘Sunuwali Buta Bosa Asomiya Paat’, ‘Suntir Suwani Lawoni Mukhkhoni’ and ‘Junbai Ei Beji Eti Diya’.

In 1962 and 1964, Dipali Barthakur recorded songs written by Bordoloi at the HMV Studio in Kolkata, in addition to few other songs. Earlier Dipali Barthakur recorded the song of the film ‘Lachit Borphukan’ in Kolkata. The song ‘Joubane Amoni Kare’ became a huge hit. After that, she rendered that famous song written and tuned by noted lyricist Kamal Hazarika – ‘Chenai Moi Jao Dei, Bihute Ahim Oi’. When Hazarika returned from London to Assam, Dipali Barthakur met him and asked for his permission to record the song. When Kamal Hazarika heard the song in her voice, he was absolutely bowled over. The song had made Assam’s boys and girls go absolutely crazy. Barthakur had accumulated a mass of obsessive, adoring fans. During the mid sixties, Dipali Barthakur selected two songs tuned by eminent artiste Birendra Nath Dutta for recording in Kolkata – ‘Ethengiya Bogoli Hoi Nache’, penned by distinguished poet-litterateur Navakanta Barua, and ‘Konman Boroshire Chip’, written by Jayanta Barua. Another song ‘Ai Nadir Epare Haahir Phool Phule’ written by Ratna Ojah became immensely popular. A number of her songs like ‘Aai Moi Sunisu Aghunot Bule Patiso Toi Mur Biya’, ‘Agoli Kolapat Lore Ki Sore’, ‘Konman Boroshire Chip’, ‘Tare Agot Ronga Jiya Rajkanya Nache Diplip’, ‘Samai Pale Aamar Phale Abar Ahi Jaba’, among others, explore women’s feelings and emotions. Although her output is relatively small, very few singers in the twentieth century achieved as much impact as Dipali Barthakur.

The spontaneity and effortlessness with which she rendered songs astounded everyone. Although she had no formal training, her music sense was incredible and she hardly needed a tanpura or harmonium to catch up with the scale. Neither did she require a tabla to catch up with the rhythm. Her style of singing was free from any influence. There was no artificiality in her voice. Her throwing and pronunciation was entirely pitch perfect and clear. There was an ethnic sweetness in her singing, perfectly irresistible, which was absolutely free and open that immediately touched the soul. It was amazing that at such a tender age, she was able to shower her songs with such genuine and deeply felt emotion.

Chronic Motor Neuron – the disease that she was afflicted with, was first detected in 1968. Then Dipali Barthakur used to stay with her elder brother Bhupendra Nath Borthakur. “One day, she had slipped down from her verandah and told us that she did not have any strength in her legs. She also complained of respiratory and speech difficulties,” her brother recalled. She was then immediately taken to Dr Mathura Bhattacharyya, the principal of Assam Medical College in Dibrugarh. After conducting various tests and investigation for seven days, Dr Bhattacharyya summoned her brother to confirm that Dipali Barthakur was suffering from a rare disease that has no medicine to cure it. Dr Bhattacharyya explained that the disease called ‘Chronic Motor Neuron’ is seen once in a billion. The patient gradually loses all strength for any movement; the entire body dries up, loses appetite and slowly becomes unable to talk properly. Her brother also received a letter from heart specialist Dr. Dhaniram Barua, who wrote that he was practicing in a big hospital in Edinburgh, and that she should be sent there. He would take every other care so that she would get proper treatment. So, Dipali Barthakur went there alone. She had undergone a small operation there. But finally, the doctors in that hospital in Edinburgh had confirmed Dr Mathura Bhattacharyya’s diagnosis and Dipali came back home. Before that, she had visited Kolkata for treatment. Back home in Tezpur, she used to take regular medicines for temporary relief and the process continued unabated. In 1969, Dr. Bhupen Hazarika penned a particular stanza as a spontaneous after-thought in the immortal ‘Shitore Shemeka Raati’, where he pays a poignant ode to the Nightingale of Assam – ‘On a damp wintry night, Let me be the nectar-voice, For an immortal song unsung as yet, That can ring in a new morn, Of a singer who has been throttled…’. Despite her condition, Barthakur somehow managed to record her last song ‘Luito Nejabi Boi’, in the same year.

“One day, I got a letter from my cousin, famous playwright Mahendra Barthakur, who wrote that an artiste wants to marry Dipali,” recalled Bhupendra Nath Barthakur. It was on an evening of 1975, when fine arts artist and Lalit Kala Akademi member Neel Pawan Baruah, son of renowned Assamese writer Binanda Chandra Baruah, told Mahendra Barthakur that he wished to marry Dipali. The playwright was taken aback and looked at his eyes for some moments. Dipali was no more that famous singer Dipali Barthakur. She could not even walk properly. “Don’t take any such decision out of emotion. Because, if one day the emotion is finished and you would think that you have made a mistake, all of us will be tremendously hurt,” Neel Pawan Baruah was told in no uncertain terms by Mahendra Barthakur then. Moreover, if she found out that he was doing her a favour out of pity or sympathy, it would be a fatal shock for her. But Neel Pawan Baruah was firm on his decision. And on March 7, 1976, Dipali Barthakur and Neel Pawan Baruah got married. Mahendra Barthakur’s father Lakshminath Barthakur performed the job of kanyadan.

Dipali Barthakur had accepted her situation as her second life. She tried her best to adjust with her physical and mental condition from the very beginning of her distressful life. She was well aware of the fact that she had to live the life alone and on somebody’s obligation. But all of a sudden, a new chapter began and her life took a new turn. Like a true partner, Baruah took care of his spouse like a mother tending to her child. Throughout their marriage, he regularly bathed her, watched over her, fed her and never let her go out of his sight. He once said that his devotion towards his wife was a part of his artistic endeavour. In doing so, he had to take some breaks from his creative pursuits. But the couple had to struggle a lot to make ends meet. They started a small eatery in the Assam State Museum premises, in 1984. They used to travel by city buses in the morning, running the canteen all day long before returning home in the evening. One day, their bus had an accident and Dipali Barthakur was admitted to a hospital. After that, they left the canteen business, and bought rickshaws. Gradually, they became the owner of as many as nine rickshaws. But some recurrent trouble compelled them to sell the rickshaws. Then, they bought autorickshaws, but then again, trouble ensued and they had no option but to sell them. Much to their relief, Dipali Barthakur and Neel Pawan Baruah received artistes’ pensions in 1988 and 1989, respectively. With that money and sometimes by selling his paintings, the couple somehow managed to sustain themselves. They never craved for anything materialistic, but only wanted peace and understanding. In 1991, Neel Pawan Baruah started an art school in the premises of their home in Beltola – Basundhara Kala Niketan. It was quite a solace and pleasure for her to see little kids coming in droves to the art school.

Even though she could no longer sing, she was very much present in the world of songs and music. She regularly used to listen to all the Assamese musical programmes of AIR, Guwahati. A genuinely good singer always deeply impressed her. Similarly, a promising singer made her enchanted. She had anticipated bright future in the singing quality of her niece Sangita or for that matter, Manjyotsna Mahanta or Tarali Sarma. She was never inhibited in showing her appreciation for bright talents. It was one of her greatest qualities as a human being. She would occupy herself with whatever was around her and not for once complained or regretted the fact that she could no longer sing anymore. But she was quite concerned to see singers, musicians and lyricists tempering with the flavour or purity of our cultural roots in the name of modernity. She once raised the topic with Mahendra Barthakur – “Brother, how a rootless tree will grow up?” Her elder brothers, Bhupendra and Bhabendra have made indispensable contributions throughout her music life. Bhabendra Barthakur died in 2009. She was stunned for quite some time and felt tremendously disenchanted. Her brother’s tune was the soul of most of her songs. Bhupendra Nath Borthakur, her elder brother, passed away in 2018, which brought back feelings of sadness and hopelessness.

Dipali Barthakur’s passing has been described in various quarters as the end of an era. But it has solidified the legend that had already begun during her lifetime. The love and affection she had received in her life is unparalleled. She will be forever engraved in the hearts and minds of millions of her fans and admirers. Dipali Barthakur’s birthday on January 30 is celebrated by people since 2002.